LOST IN CERTIFICATION

How forest certification greenwashes Samling's dirty timber and fools the international market

Prepared and published by

THE BORNEO PROJECT AND BRUNO MANSER FONDS

This report is a joint investigation by The Borneo Project and Bruno Manser Fonds.

Disclaimer: This report has been prepared in good faith on the basis of information available at the date of publication. The authors do not guarantee that all information is complete: readers are responsible for assessing the relevance and accuracy of the content of this publication. The authors will not be liable for any loss, damage, cost or expense incurred or arising by reason of any person using or relying on information in this publication.

Publication date: November 15, 2023.

Unless otherwise stated, all photos are property of The Borneo Project, Bruno Manser Fonds or Canva stock. Unless otherwise stated, satellite images are sourced from Bruno Manser Fonds archive, Sentinel-2 2020 by EOX - 4326 and Google Earth (Maxar TechnologiesLandsat / CopernicusCNES / Airbus), accessed 2023.

Citation: The Borneo Project & Bruno Manser Fonds, Lost in Certification: How Forest Certification greenwashes Samling's dirty timber and fools the international market, November 2023.

List of Acronyms

BHS: Baram Heritage Survey

BKJ: Ba’i Keremun Jamok

CB: Certification Body

CH: Certificate Holder

CRC: Community Representative Committee

CUZ: Community Use Zone

EUDR: European Union Resolution on Deforestation-free Products

FDS: Forest Department Sarawak

FMCLC: Forest Management Certification Liaison Committee

FMU: Forest Management Unit

FPIC: Free, Prior, and Informed Consent

FPMU: Forest Plantation Management Unit

FSC: Forest Stewardship Council

GCRAC: Gerenai Community Rights Action Committee

GFS: Global Forestry Services

HCV: High Conservation Value

IAF: International Accreditation Forum

ITTO: International Tropical Timber Organization

ISO: International Organization for Standardization

LPF: Licenses for Planted Forests

MDF: Medium Density Fiberboard

MTCC: The Malaysian Timber Certification Council

MTCS: Malaysian Timber Certification Scheme

NCR: Native Customary Rights

NGO: Non-governmental Organization

NREB: Natural Resources and Environment Board of Sarawak

PEFC: Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification

RM: Malaysian Ringgit

RSPO: Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil

SIRIM: SIRIM QAS International

SLAPP: Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation

STLVS: Sarawak Timber Legality Verification System

UBFA: Upper Baram Forest Area

Task

Start date

List of Figures

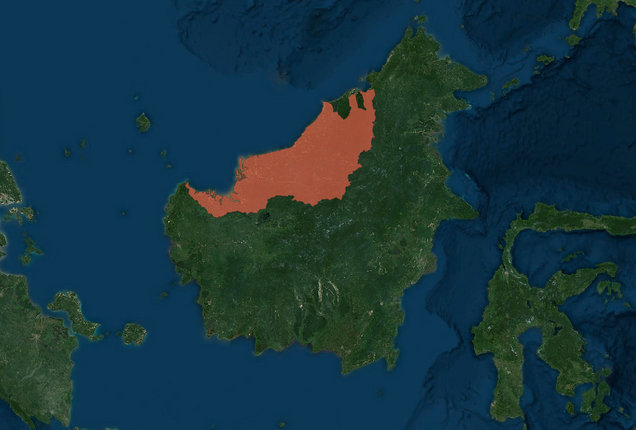

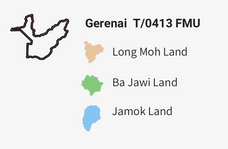

Figure 1: The Malaysian state of Sarawak on the island of Borneo

Figure 2: Entities in forest certification processes in Sarawak

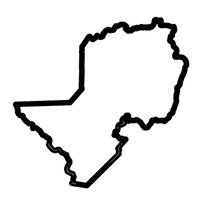

Figure 3: Samling's licenses for timber, planted forest and oil palm in Sarawak

Figure 4: MTCS status of Samling’s licenses for planted forest (LPFs)

Figure 5: MTCS status of Samling’s logging concessions and respective FMUs

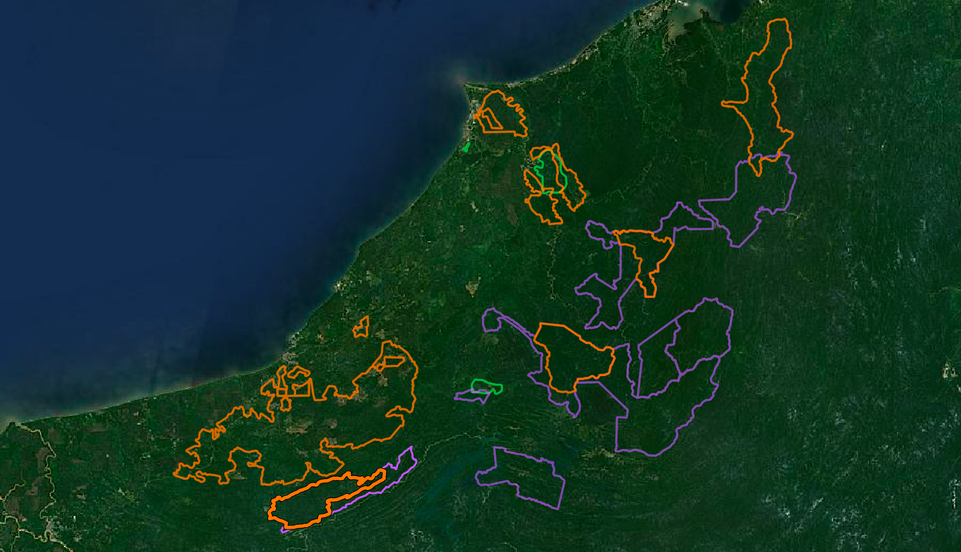

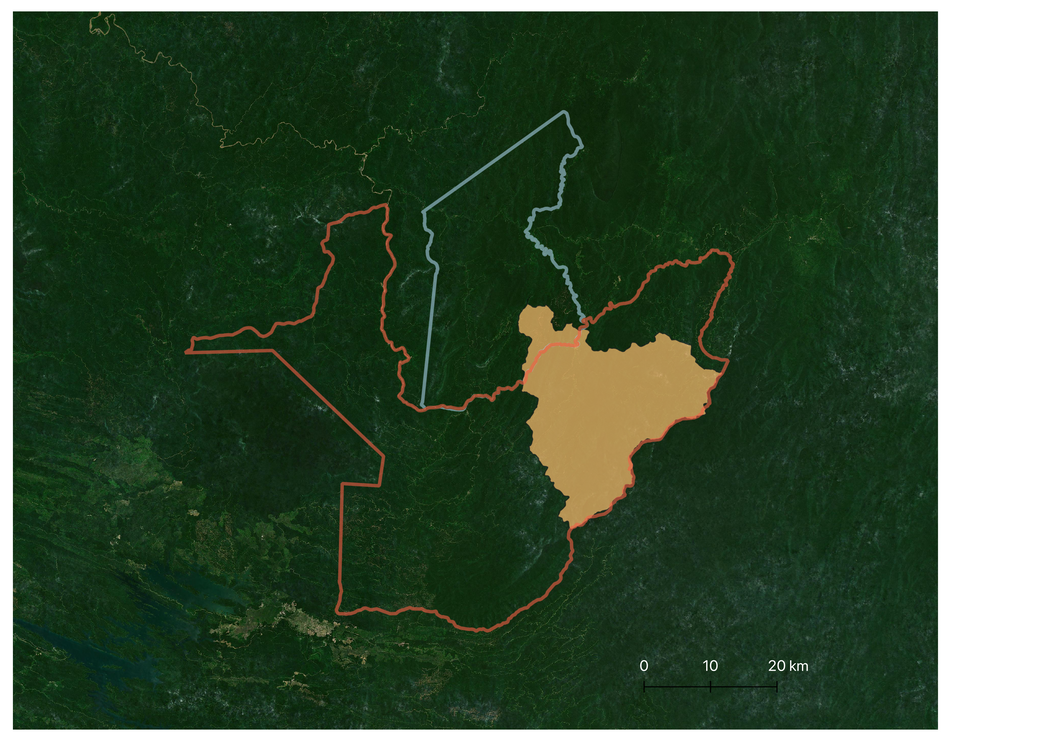

Figure 6: Overview of Samling FMUs and community territories

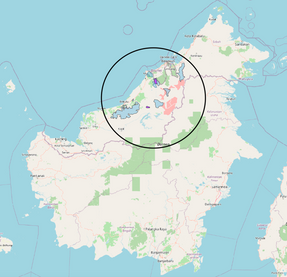

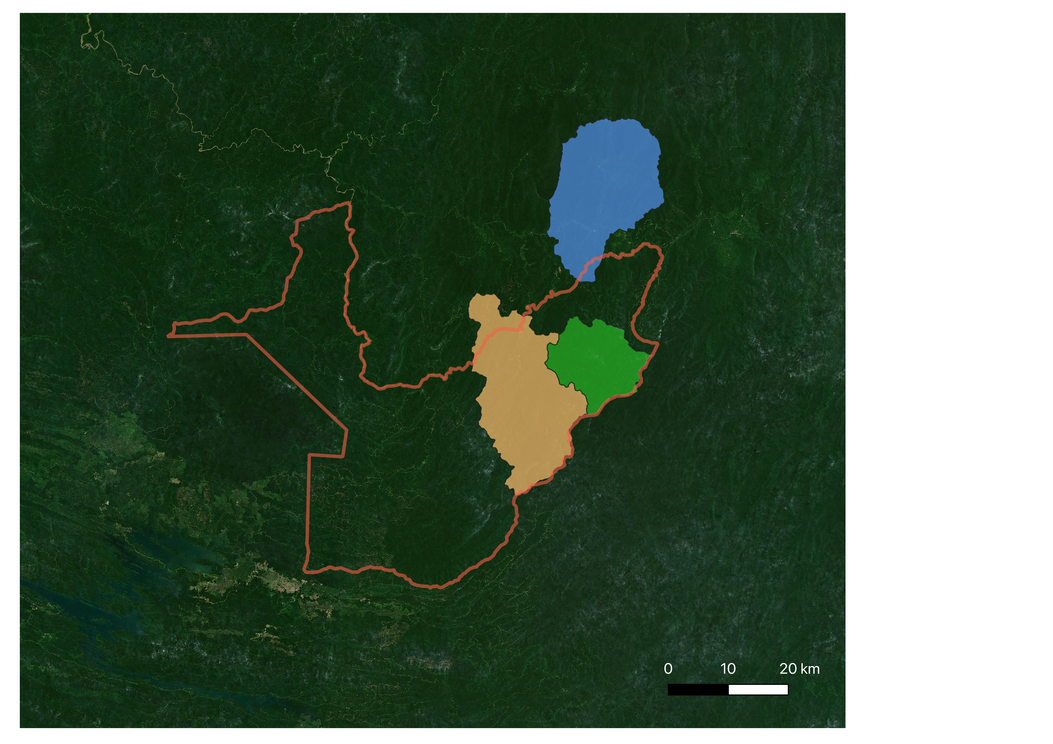

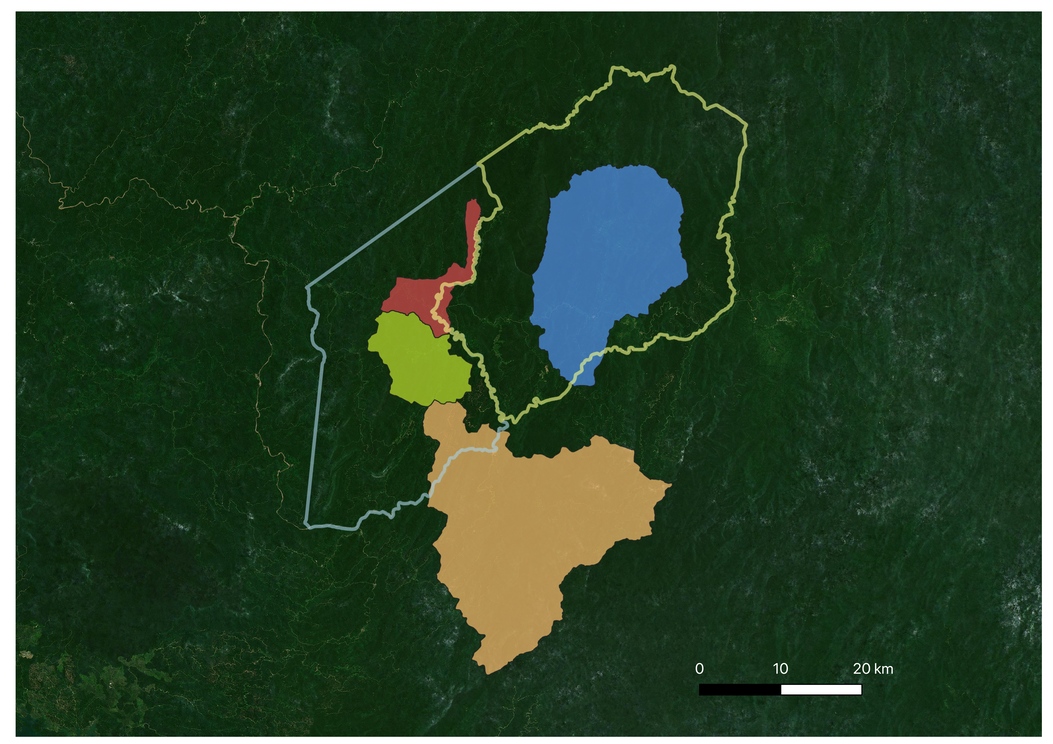

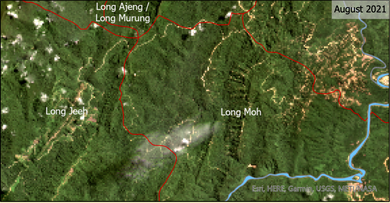

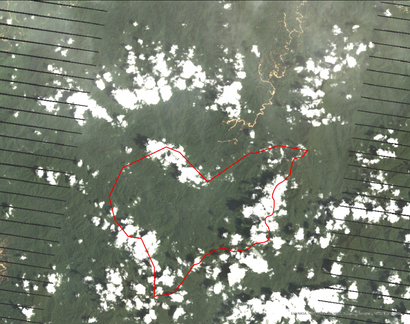

Figure 7: Gerenai FMU and overlapping community territories

Figure 8: Logging activity in and around Jamok territory

Figure 9: Before and after logging in Ba Jawi territory

Figure 10: Layun FMU and overlapping territory

Figure 11: Samling’s logging roads before April 2022 and after July 2022

Figure 12: Ravenscourt FMU and overlapping and nearby community territories

Figure 13: Analysis of Samling map vs Penan proposal

Figure 14: Suling Selaan FMU and overlapping and nearby community territories

Figure 15: Analysis of logging road encroachment

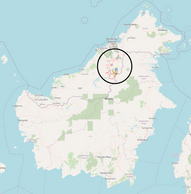

Figure 16: UBFA, Samling FMUs and community territories

Figure 17: Encroachment near the Batu Siman mountains

Figure 18: Long Moh territory overlapping with Gerenai and Suling Selaan FMUs

Figure 19: Analysis of logging activities In Long Moh 2017-2021

Figure 20: Historical location of Sungai Moh Wildlife Sanctuary

Figure 21: New location of Sungai Moh Wildlife Sanctuary

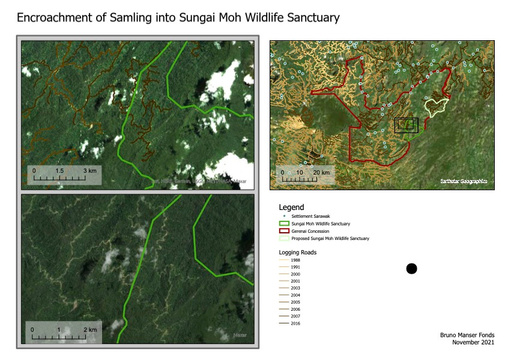

Figure 22: Progression of logging in the proposed Sungai Moh Wildlife Sanctuary

Figure 23: Analysis showing encroachment into both old and new locations of the sanctuary

Figure 24: Analysis showing encroachment into the new location of the sanctuary

Figure 25: Extensive deforestation in excised area of Gerenai FMU

Figure 26: Issued Provisional Leases showing the names of 13 different companies with a total land bank of just over 50,000 hectares

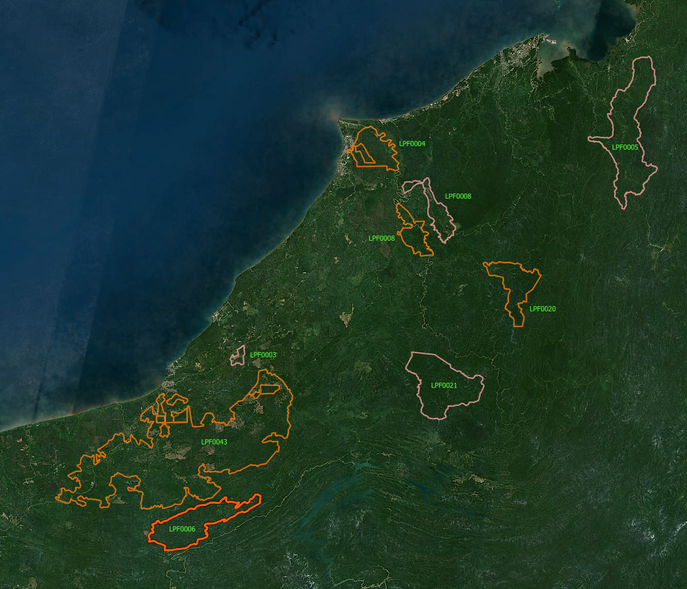

Figure 27: Samling's LPFs in Sarawak according to available data

Figure 28: Table from the Social Impact Assessment from 2018 Gerenai FMU

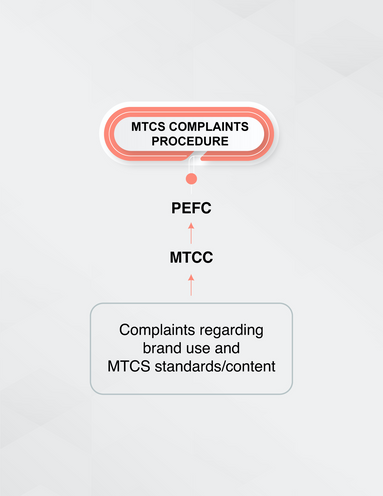

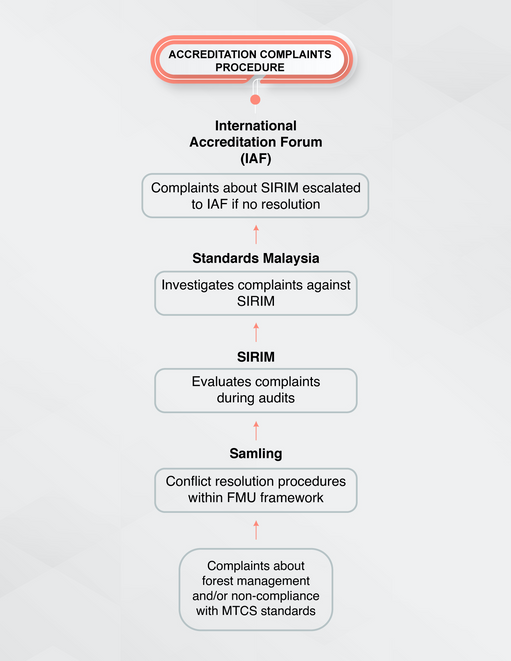

Figure 29: Complaints escalation processes

Figure 30: Accreditation complaints procedure

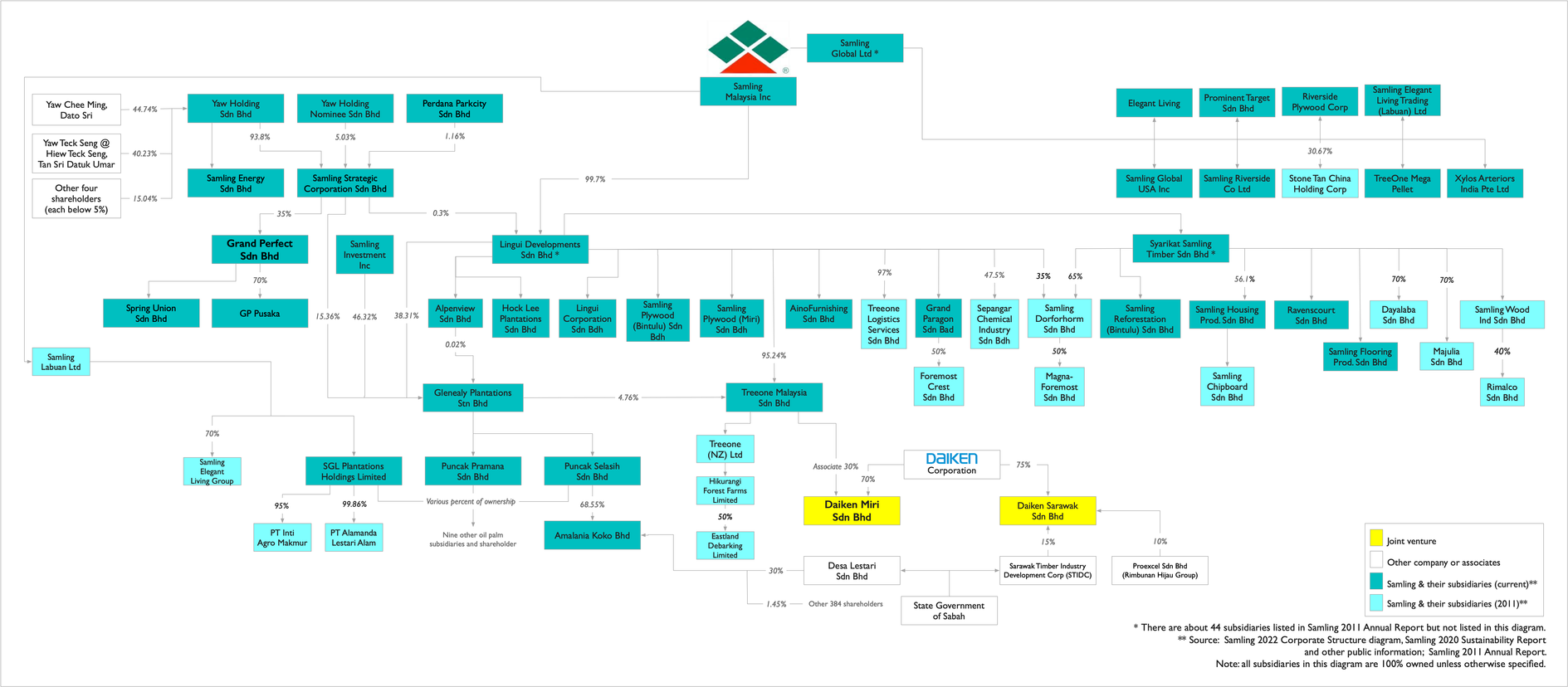

Figure 31: Samling’s corporate structure

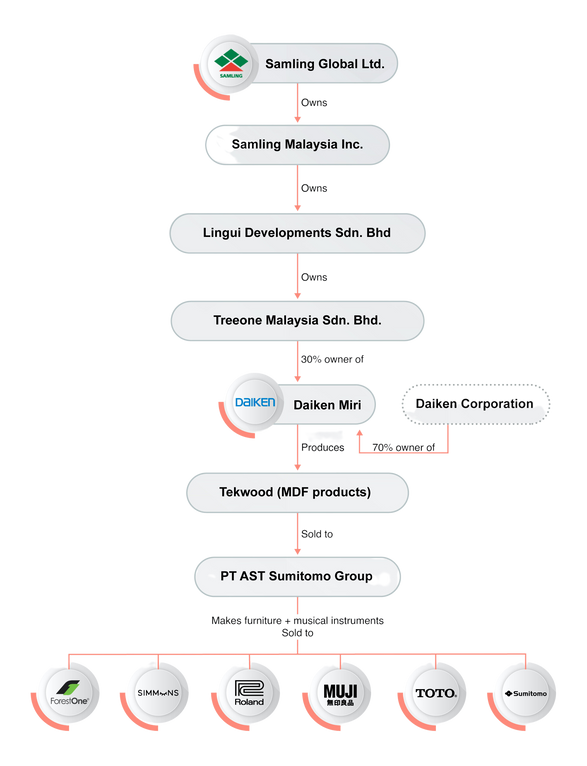

Figure 32: Product trade flow

Figure 33: Samling’s tier 1 customers

About This Report

This report focuses on the logging operations of Malaysian timber company Samling Global Limited and its subsidiaries (“Samling“) in Sarawak from 2018 to 2023.

It includes documented evidence and investigation into Samling’s:

- Ethical, environmental and compliance issues

- Conflicts with Indigenous communities

- Questionable environmental practices

- Corporate structure and global trade flow

This report also examines problems with the Malaysian Timber Certification Scheme’s (MTCS’s) complaints procedure and demonstrates how the grievance mechanisms available to impacted local communities are faulty at best, and designed to fail at worst.

Indigenous communities in Sarawak have exhausted official complaint mechanisms with little impact. They have been speaking out publicly against Samling’s logging operations since 2020, uniting under the banner of the #StopTheChop campaign. This report gathers those community claims against Samling for the first time.

In doing so, this report intends to alert Malaysian and Sarawakian authorities, importing countries, buyers, certifiers, auditors and the public to Samling's questionable practices. It also sounds the alarm about the bodies involved in forest certification in Malaysia, which have been unable to guarantee the standards that they claim to uphold and unwilling to take action to protect Indigenous rights.

Key Findings

1.

Samling has been and remains party to multiple ongoing conflicts with Indigenous communities in Sarawak regarding failure to adequately obtain Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) in their logging operations.

2.

Samling has repeatedly contributed to significant environmental degradation in Sarawak.

3.

The Malaysian Timber Certification Council and the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification have repeatedly failed to guarantee their own standards and enforce compliance.

4.

As a result of repeated failed complaints, trust in domestic and international timber certification bodies has been seriously undermined.

Introduction

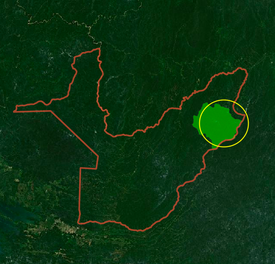

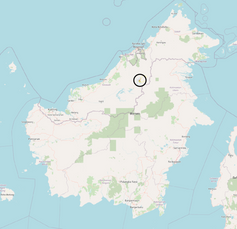

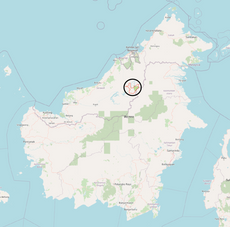

The Malaysian state of Sarawak, a biodiversity hotspot on the island of Borneo, has become infamous for its exceptionally high rate of deforestation and has been a global leader in tropical log exports.[1] A 2009 analysis found that only 11% of forests in the state had been spared from logging.[2]

The Samling group of companies is a Malaysian conglomerate with interests in timber extraction, oil palm plantations, property development, and the automotive business in a number of countries.[3] Yaw Teck Seng, the founder of the group, started the original logging business in Sarawak in 1963. Today, through three subsidiaries under Samling Global Limited, a holding company that was incorporated in Bermuda and is now registered in Hong Kong, the company controls over 65 companies related

to forest products, plantations, and logging. The Yaw family has extensive political ties and their companies have repeatedly come under fire for alleged environmental and human rights conflicts in Malaysia and beyond.

Samling is one of the “Big Six” logging companies, which have dominated Sarawak’s timber boom for decades. Starting with timber extraction in the watersheds of the Baram and Limbang rivers, Samling is now the largest timber concession and forest plantation holder in Sarawak, managing over 1.1 million hectares of forest land and almost 200,000 hectares of forest plantations.[4] The conglomerate has been active in multiple global hotspots of deforestation, including Papua New Guinea, Indonesia, and Guyana.[5]

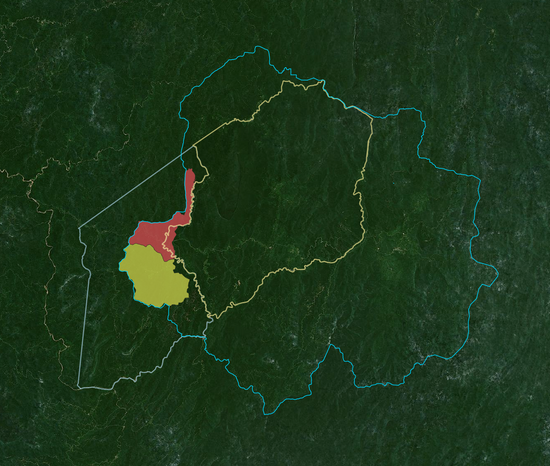

Figure 1: The Malaysian state of Sarawak on the island of Borneo

N

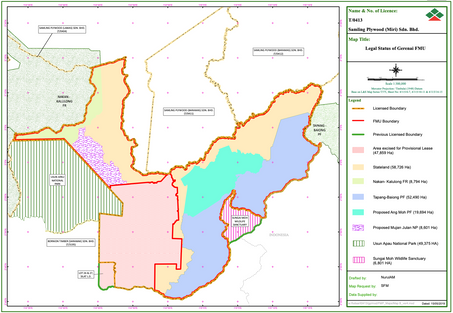

Samling operates its upstream operations in Sarawak via numerous different legal entities whose management, operations and branding are closely coordinated and controlled by Samling's operational headquarters in Miri, Sarawak. In this report, they are collectively referred to as 'Samling' rather than the individual legal entities' name. Samling subsidiaries examined in this report include but are not limited to Samling Plywood (Miri) Sdn Bhd, Samling Plywood Baramas Sdn Bhd, TreeOne Megapellet Sdn Bhd and Ravenscourt Sdn Bhd all of which are private companies registered with the Malaysian Companies Commission.

Reports of illegal logging, conflicts with traditional and Indigenous communities, and deforestation by Samling and its related companies have been circulating for many years:

- A Global Witness report from 2011 includes allegations of illegal logging by Samling going back to 1998.[7]

- The Norwegian Government Pension Fund divested from Samling Global in 2010, after an investigation found significant evidence of “illegal logging and severe environmental damage” in their forest operations in Sarawak and Guyana.[8]

- In 2011, Concord Pacific, a company linked to Samling’s founder Yaw Teck Seng as the controlling shareholder (60%),[9] was fined $100 million for illegal logging in Papua New Guinea.[10]

- In May 2023, the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) accepted a complaint filed against Samling for alleged illegal logging, violations of human rights, destruction of High Conservation Value (HCV) forests, and breach of land conversion standards.[11]

"Sarawak is the worst example of tropical rainforest deforestation that we have seen anywhere in the world"

— Explorer Sir Robin Hanbury-Tenison speaking at the Basel Rainforest Tribunal, August 2023 [6]

The Sarawak government is working towards establishing sustainable logging practices in depleted forests, making forest certification mandatory for all logging concessions. This initiative has forced Samling to obtain forest certification for its timber extraction operations. However, the evidence provided in this report indicates that Samling has not fundamentally altered its practices to enhance sustainability and address ethical concerns.

Despite driving deforestation and exploiting the resources of local communities, Samling is able to export so-called “sustainable” timber around the world under the guise of forest certification. The Malaysian Timber Certification Scheme (MTCS) facilitates this process, essentially greenwashing the supply chain.

Land Rights in Sarawak: Inherent Risk

Timber from Sarawak is inherently high-risk from a human rights point of view.

Logging operations in Sarawak have been met with Indigenous resistance for decades, including massive blockades erected by Indigenous communities since the early 1990s in the north of the state, where Samling is the main timber logging concession holder.

The state of Sarawak simultaneously acknowledges Indigenous land rights while limiting them in a variety of ways.[12] Indigenous communities have extensive traditions and customs, or adat, regarding land rights, and each community is considered to own a territory. This is legally referred to as Native Customary Rights (NCR) land.

While the state has acknowledged that there are between 1.5 and 2.8 million hectares of NCR land in Sarawak, they have not revealed where exactly the NCR land is. Instead, laws relating to Indigenous land rights and NCR have been progressively tightened to the detriment of Indigenous rights.[13]

Many communities have tried to gain official legal recognition of NCR land through expensive court cases that often last many years, sometimes decades. Under the Sarawak Land Code, communities must prove they have used an area uninterruptedly since before 1958, which is challenging for longhouse communities and even more so for traditionally nomadic communities like the Penan. While they have, of course, used the land for much longer than that, much of that use has left no documented evidence. Amendments to the Land Code and recent case law arguably restrict the rights of communities to their NCR land even further.[14] Ironically, by bringing NCR claims through the proper legal channels, communities now risk handicapping their own rights to access their traditional territories. These are just some of the many elements discouraging communities from attempting to gain legal recognition over their land.

Moreover, the state of Sarawak keeps important land registry information hidden from public view, such as the locations and title holder information of logging and plantation concessions and NCR land.[15]

These elements make it easier for companies to gain access to land that should be recognized as NCR land, resulting in repeated encroachment and land conflicts with Indigenous communities, and creating an inherently high-risk environment for companies claiming to or attempting to respect Indigenous rights.

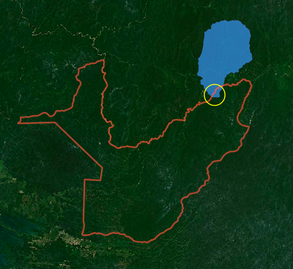

Community Conservation Initiatives

Indigenous communities in Sarawak have many traditional customs regarding forest resource management, including protection measures and communal land-use planning. In recent years communities have taken steps to gain formal recognition of Indigenous-led forest protection in certain areas.

One of these initiatives is known as the Upper Baram Forest Area (UBFA), sometimes referred to as the Baram Peace Park or the Baram Heritage Forest. The UBFA is an initiative designed to increase forest protection and build regenerative livelihoods in the upper Baram area. It was originally proposed by Indigenous communities in the area. In December 2020, the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO) endorsed a proposal submitted by the Forest Department Sarawak (FDS) for the project, which covers 2,835 square kilometers. The project has since been financed by ITTO member countries, the Swiss city of Basel, and Switzerland-based Bruno Manser Fonds.

The Sarawak government is currently working with local stakeholders, including Indigenous communities, KERUAN Organisation, and SAVE Rivers, to define and launch the project.[16]

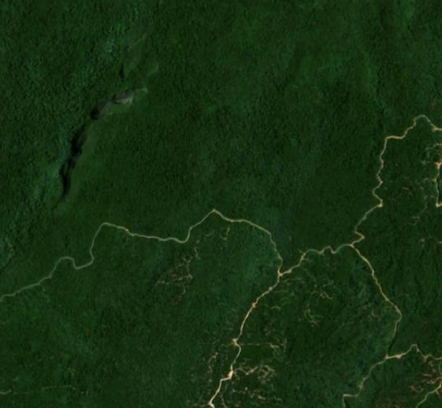

In 2019, the Kenyah Jamok communities of Long Tungan and Long Siut submitted a proposal for official recognition of their communal forest, the Ba’i Keremun Jamok (BKJ), to FDS. Jamok ancestors recognized the area as a protected zone when they moved to Long Tungan many generations ago, and no part of the BKJ has ever been cultivated. It is also located within the UBFA area. When Samling trespassed in the area in 2018, the community was motivated to submit documents for official recognition of the BKJ in order to prevent further timber extraction.

Many communities in the area are currently in the process of developing similar plans to achieve formal recognition of important communal forest areas for protection and conservation.

Forest Management Units and Logging Concessions

- A Forest Management Unit (FMU) or a Forest Plantation Management Unit (FPMU) is a designated area of natural or planted forest managed by a specific entity or company for timber extraction and other forest-related activities. It is a defined parcel of land where forest management practices take place under explicit objectives and according to a long-term management plan.[17] This can include logging concessions or plantation concessions.

- A License for Planted Forest (LFP) refers to the authorization or contract granted by the government or relevant authorities to a specific company or individual allowing them the right to plant, manage, and harvest a forest plantation, such as acacia, eucalyptus, and other species harvested for timber. LPF license holders are also allowed to plant up to 20% of the plantable area of an LPF with oil palm trees.[18]

- A logging concession refers to the authorization or contract granted by the government or relevant authorities to a specific company or individual, allowing them the right to extract timber and engage in logging activities within a designated area of forest land (FMU). The concession typically outlines the terms and conditions under which the logging activities can take place, including the duration of the concession, the permitted volume of timber extraction, the exact location where timber may be cut at a certain time (coupes), and the environmental and social obligations that the concessionaire must adhere to during the logging operations. The focus of a logging concession is primarily on the rights and responsibilities of the concessionaire to exploit timber resources within the approved area.

Timber Certification and Logging in Sarawak

In 2017, the Forest Department Sarawak adopted the policy that all long-term FMUs in Sarawak are required to be certified by the end of 2022, with a grace period of two years.[19] The intention behind certification is to ensure basic standards for sustainability. There are two certification options for FMUs: through the Malaysian Timber Certification Scheme (MTCS), which is in turn certified by the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC), or through the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). The Forest Department of Sarawak has also declared that all LPFs must be certified by 2025.[20]

PEFC and FSC are both international non-profit organizations that promote sustainable forest management through certification. The FSC certification process involves an independent assessment of forest management practices

against a set of environmental, social, and economic standards established by the FSC. It also ensures compliance with local policies regarding logging. Currently, there are no FSC-certified FMUs in Sarawak.

The MTCS is a national forest certification system developed by the Malaysian Timber Certification Council (MTCC), a private company with close connections to the Malaysian government and timber industry. It focuses on verifying the sustainable management of forest resources and ensuring that timber products meet international sustainability standards. It also ensures compliance with FDS regulations regarding timber extraction. The MTCC is responsible for the operation and credibility of the MTCS as a scheme recognized by PEFC. FMUs that undergo MTCS certification must comply with MTCC's specific criteria and guidelines for sustainable forest management.

In Malaysia there are two Certification Bodies (CBs) – entities that can evaluate and certify FMUs and timber companies against the MTCS standards for forest certification: SIRIM QAS International (SIRIM) and Control Union.

SIRIM is a government-owned corporation responsible for promoting, maintaining and inspecting standards in various industries. Control Union is an international certification and inspection organization that provides independent assessment and certification services in a range of sectors.

Figure 2: Entities in forest certification processes in Sarawak

Figure 3: Samling's licenses for timber, planted forest and oil palm in Sarawak

N

Samling licenses for planted forest

Samling licenses for timber

Samling licenses for oil palm

Certification Bodies conduct three stages of audits for MTCS certification of FMUs: stage 1, stage 2, and surveillance audits. The first stage, known as the pre-assessment, evaluates the FMU's forest management system and identifies any major gaps or “non-conformities” to the standards. The main assessment, or stage two audit, involves comprehensive on-site inspections and reviews to assess the FMU's compliance with sustainability criteria related to environmental, social, and economic aspects of forest management. After initial certification, regular surveillance audits are conducted to monitor ongoing compliance. A re-certification audit is conducted before the certificate expires.

In the context of FMU management, a Community Representative Committee (CRC) is a forum organized by the company holding the timber license that facilitates communication and engagement between representatives from both the FMU management personnel and the local communities impacted by its activities. Forest Department Sarawak sustainable management guidelines and manuals require FMU management to organize CRCs in all FMUs, and specifies that communities must choose their own CRC members and the number of community representatives. The committee aims to foster effective communication, engagement, and collaboration between these stakeholders.

Several of Samling’s FMUs have been certified through the MTCS. This includes Samling's Ravenscourt and Gerenai FMUs, which were certified under MTCS in 2018 and 2020, respectively. According to an email sent to The Borneo Project from the MTCC’s Director of Forest Management on August 25th 2023, the MTCS certificate for the Ravenscourt FMU was withdrawn in July 2023 due to Samling’s failure to submit and implement effective corrective action regarding non-conformities to the MTCS standards in their FMU operations.

Of Samling’s eight LPFs in Sarawak, four were holding a certificate at the time of publication (November 2023). All of Samling’s LPFs and timber concessions in Baram contain or border lands claimed by Indigenous communities with NCR claims.

Figure 4: MTCS status of Samling’s licenses for planted forest (LPFs)*

License for Planted Forests Number | FPMU name | MTCS certified? |

0014 | Segan | Certified in 2014 |

0021 | Paong | Audit ongoing |

0004 | Kuala Baram | Certified in 2022 |

0005 | Kanaya | Unknown |

0006 | Lana | Certified in 2017 |

0008 | Marudi | Certified in 2019 |

0020 | Layun | Unknown |

0043 | Unknown | Unknown |

*Based on currently available public data.

Figure 5: MTCS status of Samling’s logging concessions and respective FMUs*

Forest Timber License Number | FMU name | MTCS certified? |

T/0280 | Ulu Trusan | Certified In 2018 |

T/9115 | ||

T/0294 | Ravenscourt | Certified In 2018 and withdrawn In 2023 |

T/0390 | Tama Abu | Audit ongoing |

T/9082 | ||

T/0405 | Layun | Audit ongoing |

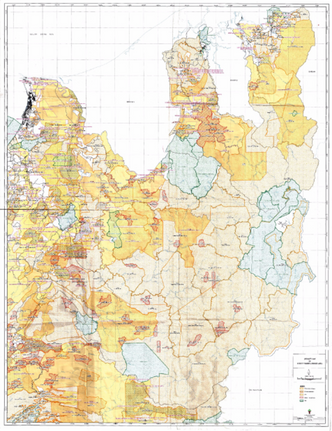

T/0411 | Suling Selaan | HCV assessment ongoing |

T/0412 | Certified by MTCS in 2004 and then expired In 2009 | |

T/0413 | Gerenai | Certified In 2020 |

T/3670 | Bah Sama | Certified In 2018 |

T/0404 | Sekiwa | Unknown |

T/3282 | Unknown | Unknown |

T/3284 | Unknown | Unknown |

*Based on currently available public data.

PART 2:

Evidence of Ethical, Environmental and Compliance Issues

Documented Conflicts with Indigenous Communities

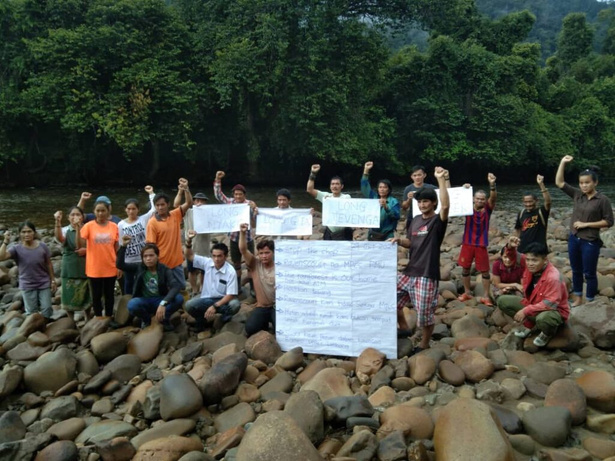

Indigenous communities in Baram protesting logging on their territories

Problems with Obtaining Free, Prior and Informed Consent

There is overwhelming evidence that Samling neglected to adequately obtain the free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) of Indigenous communities located within their logging concessions in multiple locations.

Consultations and impact assessments did not adequately or accurately inform or assess communities. In some cases, very few people were consulted, or communities were not consulted at all. Entire communities were left off of the maps for the FMUs. Among the people who were consulted, many people expressed opposition to logging.[21]*

Samling has committed to obtaining FPIC in its logging operations in multiple ways. According to a November 2021 audit by US-based Global Forestry Services (GFS), Samling “has a Social Policy dated 9th July, 2018, not to harvest any areas used by local communities until a mutual agreement has been signed.”[22] The MTCS standard also guarantees FPIC.**

The following examples highlight the situation in multiple FMUs managed by Samling. They demonstrate a pattern of failing to adequately obtain the consent of Indigenous communities, which inevitably results in conflict.

*In an EIA conducted for the Gerenai Concession in 2014, 64% of people interviewed said they had objections to the project, 27% said they were not sure about the project, and only 9% said they had no objections.

**Under principle 3.1: “Indigenous peoples shall control forest management on their lands and territories unless they delegate control with free, prior and informed consent to other agencies and/or parties.”

Overview

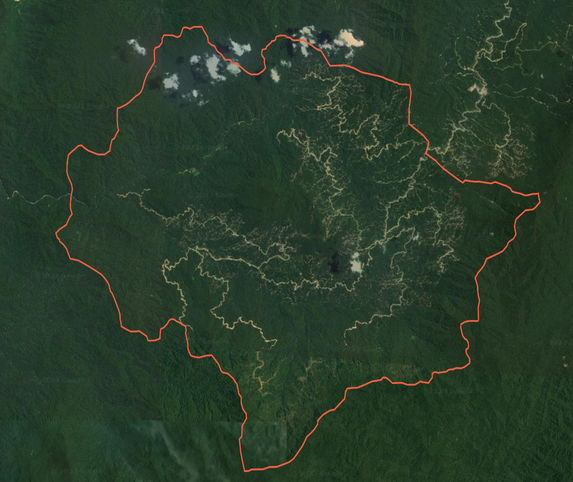

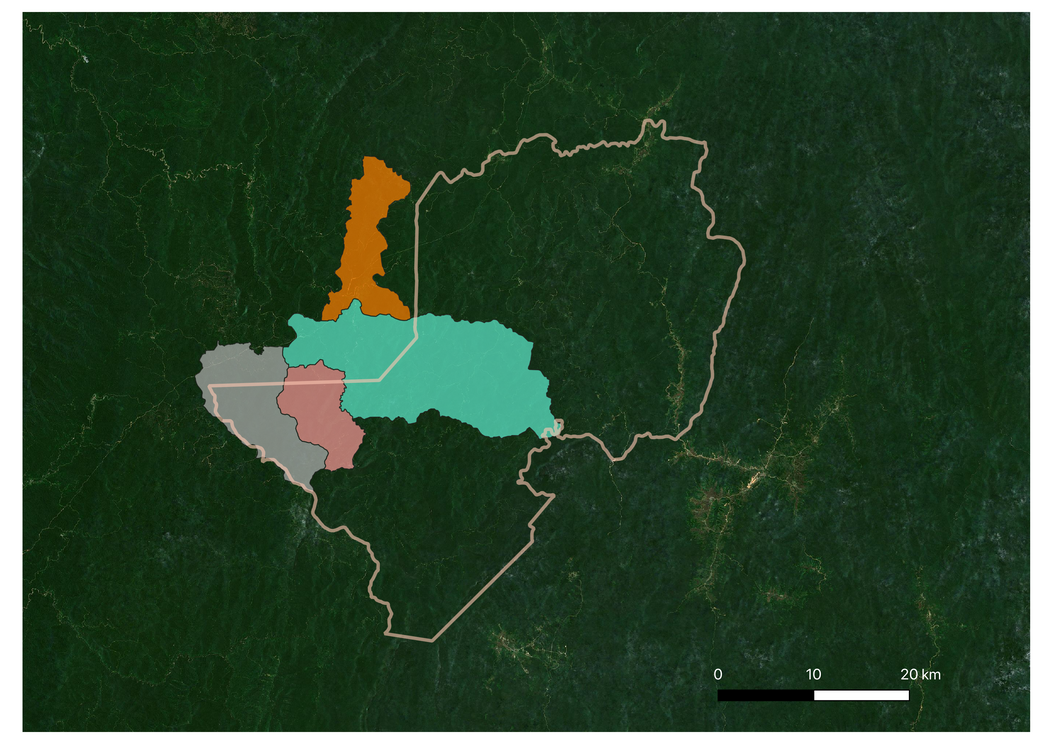

Figure 6: Overview of Samling FMUs and community territories discussed in this report

T/0294

T/0405

T/0411

T/0413

T/0412

There are many more Indigenous communities with territories that fall within the maps discussed in this report. The maps in this report only identify territories of the communities discussed.

N

Gerenai FMU T/0413

Long Moh Land*

Ba Jawi Land*

Jamok Land

Layun FMU T/0405

Long Pakan Land

Ravenscourt FMU T/0294

Long Adang Land

Ba Gita Land

Ba Peresek Land

Long Tevenga Land

Suling Selaan FMU T/0411 & T/0412

Long Lamam Land

Long Ajeng/Long Murung Land

Long Moh Land

Jamok Land

Gerenai FMU T/0413

Figure 7: Gerenai FMU and overlapping community territories

N

The Gerenai FMU has become a focal point of concern due to a lack of consultations before MTCS certification, repeated allegations of encroachment into Indigenous territories and alleged violations of community rights.

“Samling claimed that they have consulted villages within the Gerenai and that they have been given support and consent to carry out work there. The majority of us ‘kampung’ folks were left in the dark, we do not know what was agreed between the headman and Samling. Nothing was discussed with us.”

— Patrick Keheng, Long Julan [23]

Audit reports confirm community claims

Community claims that Samling failed to adequately obtain FPIC and consult communities prior to certification are well-documented in multiple audits conducted by SIRIM for the Gerenai FMU in 2018, 2019, 2021, and 2022. For example, the stage 1 audit report from October 2018 found that there were no records of consultations with local communities or Community Representative Committee (CRC) established.[24] The audit found that lists of relevant stakeholders and records of communication were not available.

Furthermore, forest managers were “not aware of the applicable federal, state and local laws, as well as the regulatory framework for forest management,” nor were they aware of “all binding international agreements relevant to forest management.”

These issues have persisted for all audits conducted to date. In the public summary of the stage 2 audit conducted in 2019, SIRIM’s auditors concluded:

“...consultation was not sufficient. Majority of the communities were not aware of the objective and function of Community Relation Committee (CRC) which is yet to be established.”[25]

Major non-conformity against indicator 2.2.2

Based on the surveillance audit from 2021, SIRIM concluded:

“Majority of the local communities don’t understand Forest Certification process including the objectives and meaning of FMU operation including formation and objectives of CRC or Forest Management Certification License Committee (FMCLC)* as there were lack of clear disclosure from the FMU. There was also inadequate community engagement, involving prior and informed consent from the communities on the FMU certification process affecting the duly recognized legal and customary or Use rights of the communities [sic].”[26]

Major non-conformity against indicator 2.2.2

“Majority of the communities in 18 villages were not aware of the mechanism available to resolve dispute.”[27]

Minor non-conformity against indicator 2.3.1

“Majority indicated the inadequate engagement, consultation and identification of the customary rights of the indigenous communities within and surrounding the FMU and meeting was held only with community leaders and headmen. There was insufficient involvement of the larger community at the village level. […] records of dialogue and consultation held with communities and relevant stakeholders on the documented customary rights of indigenous people was not available.”[28]

Major non-conformity against indicator 3.1.2

“Mechanism for conflict resolution (resource & tenure rights) were not publicly available and consultation with local communities were not conducted for 2020/2021.”[29]**

Minor non-conformity against indicator 3.3.2

*The FMCLC is a committee that includes representatives from various stakeholders involved in forest management and certification processes. Each FMU has their own FMCLC and they are only engaged when conflicts arise.

**The authors of this report note that the Covid-19 Movement Control Order MCO was a contributing factor to this failure.

These non-conformities provide evidence that SIRIM had either missed all of these problems during the 2019 audit, or that the situation had worsened, or both. Based on the surveillance audit from 2022, the auditors concluded:[30]

“The consultation held with local communities to identify and document areas traditionally used and sites of significant importance to them was not conducted. The audit team has concluded that the corrective actions provided were not sufficiently implemented…”[31]

Major non-conformity against indicator 2.2.2 reissued

“The mechanism for conflict resolution (land tenure and use rights) was not sufficient. Updated records of a dispute over tenure and use rights were also not available…the corrective actions provided were not sufficiently implemented”[32]

Minor non-conformity against indicator 2.3.1 upgraded to Major non-conformity

“The Gerenai FMU has lacked engagement and identification of the customary rights of the indigenous communities within and surrounding the FMU. Furthermore, the status of indigenous people’s control over their land and territories was still not clear. The corrective actions provided were not sufficiently implemented.”[33]

Minor non-conformity against indicator 3.1.1 upgraded to Major non-conformity

It was noted the engagement with communities within and surrounding the FMU on customary rights or user rights of lands and resources was inadequate. The engagement with communities was limited to community leaders. In addition, there was no record of delegation control with free, prior and informed consent to other agencies and/or parties available. The corrective actions provided were not sufficiently implemented…”[34]

Major non-conformity against indicator 3.1.2 reissued

“Consultation with affected local communities on a mechanism for conflict resolution (sites of special cultural, ecological, economic or religious) was not sufficient. The corrective actions provided were not sufficiently implemented.”[35]

Major non-conformity against indicator 3.3.2 reissued

These examples illustrate Samling’s incomplete and arguably inadequate community engagement processes in Gerenai FMU, even after multiple audits over a period of many years. This only intensifies patterns of conflict with local communities.

Despite these non-conformities, SIRIM has not suspended or revoked the MTCS certificate for the Gerenai FMU. The problems identified by SIRIM touch on many of the same inadequacies flagged by the communities themselves, and published on the websites of SAVE Rivers, a Sarawak civil society organization, and others. Reports on the disputed Gerenai FMU were the subject of defamation proceedings by two Samling subsidiaries against SAVE Rivers in a local court, which were retracted by Samling in September 2023.

Long Siut and

Long Tungan

In July 2018, the Indigenous Kenyah Jamok living in the villages of Long Siut and Long Tungan reported that they found Samling entering their communal forest, the Ba’i Keremun Jamok, allegedly without prior notice or the community’s consent.

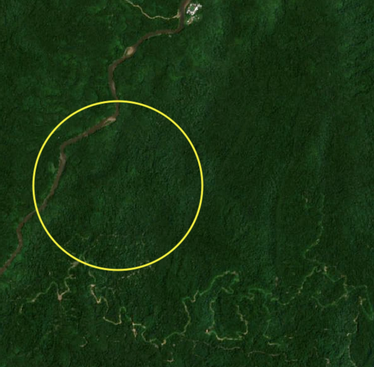

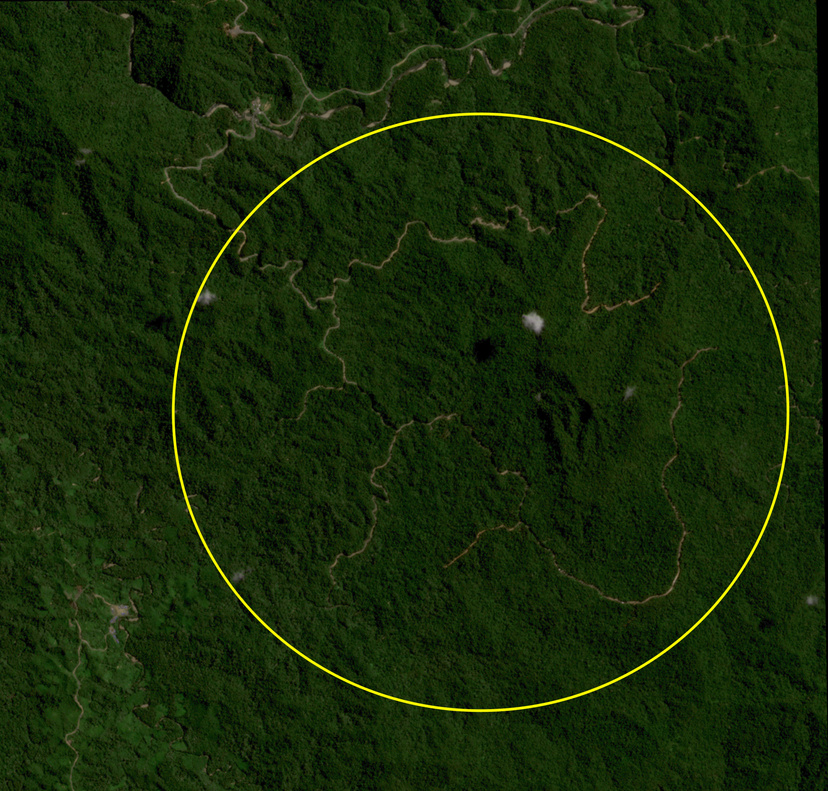

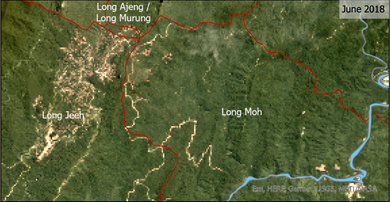

The Jamok communal forest is within the Gerenai FMU, which was not yet MTCS certified at that time, as well as within the UBFA conservation project. Satellite images show logging activities entering the communal forest in 2018 (see Figure 8).

Jamok community members sit atop

logs felled by Samling on their land in July 2018

Figure 8: Logging activity in and around

Jamok territory

Area of Interest

N

Gerenai FMU

Jamok territory

Long Tungan

The community reacted quickly, talking to Samling and informing the Forest Department Sarawak (FDS), requesting that FDS no longer grant any logging permits in their territory. According to minutes of a meeting between Samling and Jamok representatives, Samling agreed to pay the community RM 16,400 in compensation for the 107 logs taken and stopped timber extraction in the area — although they made no admission of guilt.[36]

Long Tungan residents

“We are working hard on community conservation to create long-term sustainable jobs in our forests Not to chop it all down for short-term gain”

— John Jau Sigau,

Long Tungan [37]

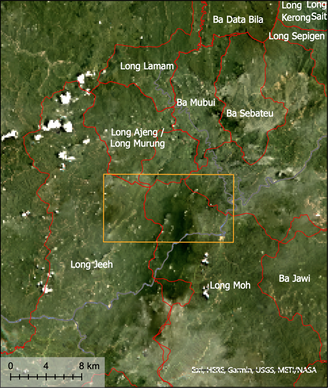

Ba Jawi

Deforestation in the territory of Ba Jawi is of special concern as this is the last Penan community in the Baram area that follows a nomadic hunter-gatherer life. Their situation needs special sensitivity regarding consultation and FPIC.

Between approximately 2012 and 2015, Samling logged the territory of Ba Jawi (see Figure 9) without obtaining the community’s prior consent. The community had also filed an NCR case against Samling in 2010.[38] Ba Jawi has repeatedly expressed their rejection of logging in letters to Samling in February 2020 and July 2023.

SIRIM’s audit reports for Gerenai document the difficulties in consulting and reaching the small, remote community. The 2021 audit identified the lack of consultations under the MTCS certification process and lack of social impact assessments (SIAs) as a minor non-conformity under indicator 3.1.1[39] and a major non-conformity under indicator 4.4.1.[40]

Marking NCR boundaries of Ba Jawi

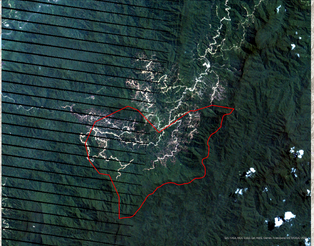

Figure 9: Before and after logging in Ba Jawi territory

Before (2010)

Area of Interest

Gerenai FMU

Ba Jawi Land

After (2015)

Members of the last semi-nomadic Penan community in the Baram: Ba Jawi

The zoning map from Samling's Forest Management Plan does not reflect the community’s demands to exclude their territory from the production zone.[41] The map instead shows an intention to build a road close to the village. The community has not been consulted about this road.

Roads are a contentious issue in Indigenous communities; while they are essential for transport and access, they also result in environmental degradation that impacts local resources, including sources of food, water, and shelter. Consultation with communities before a road is built is imperative to mitigate potential negative impacts.

“As the last nomads of Baram, we ask Samling to stay away from our forests and allow us to continue to live like our ancestors and carry on their legacy and culture.”

— Letter from Ba Jawi to Samling,

July 2023 [42]

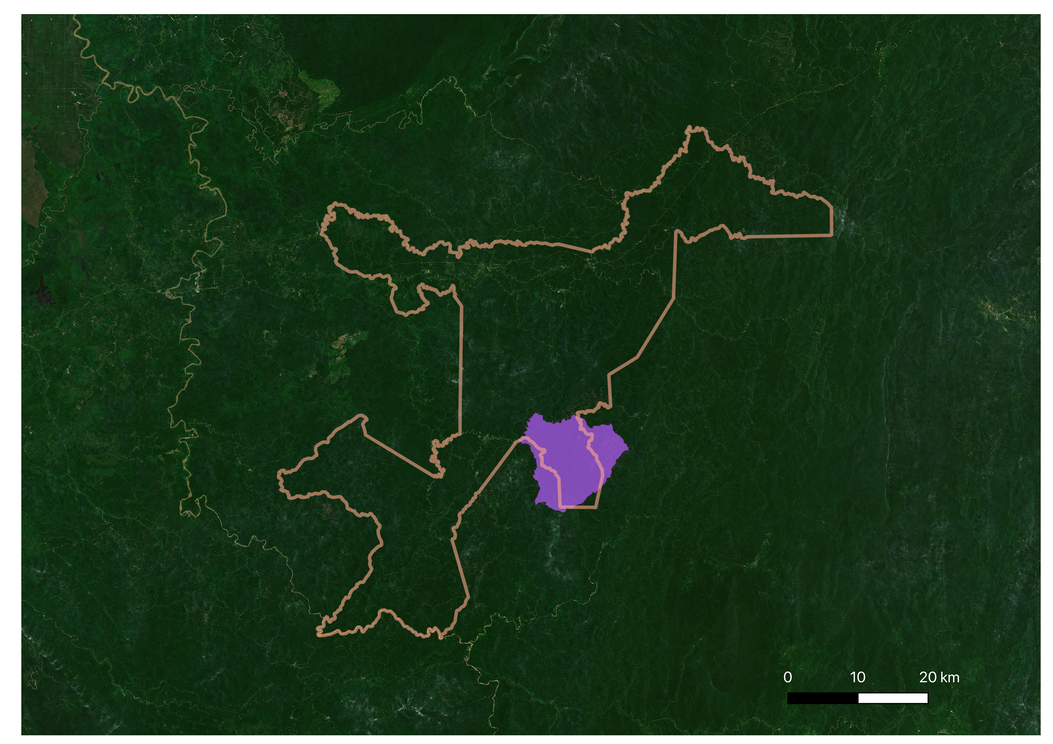

Layun FMU T/0405

Figure 10: Layun FMU and overlapping territory

Layun FMU T/0405

Long Pakan Land

N

The Layun FMU, a 142,970 hectare area, presents another example of Samling operating in Indigenous territories without prior and informed consent. As of November 2023, the stage 2 audit had been conducted by SIRIM, but the MTCS certificate had not yet been granted and the audit had not been published. Before applying for MTCS certification, the Layun FMU was certified under the Sarawak Timber Legality Verification System (STLVS) by Global Forestry Services (GFS).

The STLVS was a certification system specific to the state of Sarawak. It was established to ensure the legality of timber products originating from Sarawak's forests. GFS is a consulting and advisory firm that provides a range of services related to forestry and land-use planning. It also acted as an auditor of STLVS. Currently, the Sarawak government is requiring either FSC or MTCS certification for all FMUs, and STLVS is no longer relevant

Long Pakan blockade against Samling,

October 2021

41

Logging road encroaching into

Long Pakan territory

Long Pakan

The territory belonging to the community of Long Pakan is included in the Layun FMU (see Figure 10). When Long Pakan discovered Samling encroaching into their territory in August 2021, the community had not been consulted and had not agreed to the logging.

On August 23, 2021, the headman of Long Pakan lodged an official police report against the company. On September 22, 2021, the community erected a blockade. The headman lodged a second police report on October 5, 2021. Explaining the blockade, the headman said:

“We request Samling leave immediately and not to be given any timber certification in our area. We erected a blockade to prevent Samling from further encroaching into the NCR land of Long Pakan. We are not happy when the company continues to work because the forest will vanish, forest products are difficult to find such as sago, rattan, medicines, game is also difficult to hunt and the polluted water and soil erosion cause the fish to die.”[43]

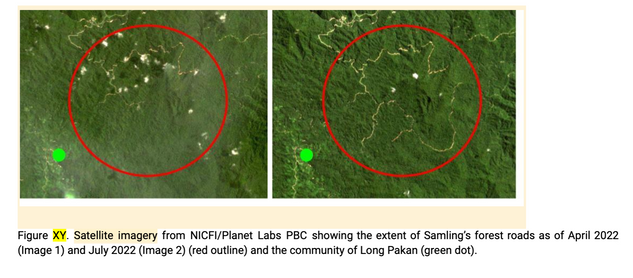

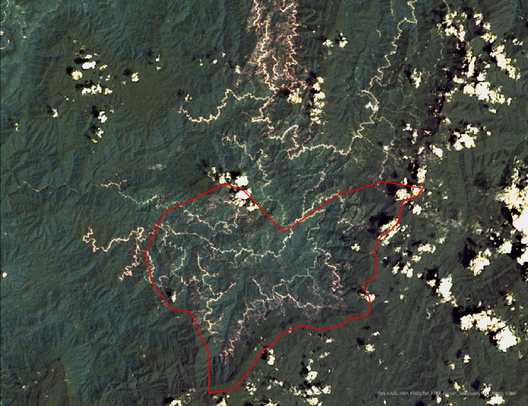

Figure 11: Samling’s logging roads before April 2022 and after July 2022

Long Pakan village location

Area of Interest

Long Pakan Land

Layun FMU T/0405

April 2022

July 2022

Long Pakan blockade

In response to media reports about Long Pakan’s resistance to logging, Samling Group’s COO James Ho Yam Kuan stated: “Samling did not carry out any logging operations in Long Pakan as the area is outside its concession area.”[44] This is directly refuted by evidence from Long Pakan community members, satellite images, and GPS coordinates taken of a logging road built into Long Pakan territory. Satellite imagery confirms the progression of the logging roads built by Samling

(see Figure 11).

The encroachment into the territory of Long Pakan in 2021 happened without the community’s agreement because Samling did not consider Long Pakan to be an affected community. GFS audits from 2019 and 2020 did not include Long Pakan in the list of affected communities.[45] Samling started negotiating with the community only after encroaching in their territory and the resulting complaints. Long Pakan was listed as a relevant village in the 2021 audit, after complaints were lodged.

The audit report states that Samling is “in the process of negotiation for the agreement” with Long Pakan.[46] Samling therefore failed to note the existence of an entire village prior to starting logging operations, clearly failing to do proper due diligence.

“Samling is denying our very existence. How can they claim that the territory of Long Pakan is not within their concession? We Penan might have no roads to our villages, but we are here and will stay.”

— Komeok Joe, KERUAN Organisation [47]

Ravenscourt FMU T/0294

Figure 12: Ravenscourt and overlapping and nearby community territories

Ravenscourt FMU T/0294

Long Adang Land

Ba Gita Land

Ba Peresek Land

Long Tevenga Land

N

Ravenscourt has long been a contentious FMU with repeated land conflicts. In 2010, Norway's Council on Ethics for the Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG) found that:

"In the Council’s opinion, there can be little doubt that Samling has acted illegally in several ways in this concession, including carrying out re-entry logging for four years without the required Environmental Impact Assessment, logging in an approved National Park which has been excluded from the official licence area and where logging is prohibited, and illegally constructing roads and conducting land-based logging in areas of steep Class IV terrain where such logging normally is banned. The Council finds it highly probable that the logging activities performed in this concession are devastating to the forest and the local biodiversity, causing extensive soil erosion and reducing the area’s value as a national park."[48]

Penan protest against Ravenscourt FMU

The Ravenscourt FMU was first MTCS certified by SIRIM in 2018. Multiple major and minor non-conformities by Samling were found in the yearly SIRIM audit reports.

The 2020 SIRIM audit report shows that one CRC for the FMU had not yet been established. This had already been flagged as an issue during the 2019 audit, and was upgraded from a “minor non-conformity” to a “major non-conformity” in the 2020 audit.[49]

The 2021 SIRIM audit noted several non-conformities such as not adequately consulting communities, not informing them of conflict resolution procedures, and not providing communities with reports and information, including:

“Stakeholder’s[sic] consultation with the local communities confirmed that records of mechanism to resolve disputes was not made publicly accessible in the local language. There were no records of dialogue and consultation held with the community and other relevant stakeholders.”

Major non-conformity against indicator 3.3.2.[50]

SIRIM suspended MTCS certification for the Ravenscourt FMU on March 28, 2023 due to Samling’s failure to submit and implement effective corrective action regarding non-conformities. The certificate was subsequently withdrawn on July 11, 2023.

Long Tevenga, Ba Peresek, Long Adang, Long Gita

In the Ravenscourt FMU, the Penan communities of Long Tevenga, Ba Peresek, Long Adang, and Long Gita were not aware of the certification process, did not give consent for their territories to be logged, and documented their objection to logging. MTCS certification was granted in June 2018, but it was not until 2020 that some community members became aware of the certification process and reacted.

They expressed their objection to logging in a September 2020 letter to SIRIM. KERUAN Organisation sent the letter, stating that the communities of Long Tevenga, Ba Peresek, Long Adang and Long Gita, who are within or close to the border of the Ravenscourt FMU, were not aware that the area was certified for sustainable timber under the MTCS, and object to logging: “We, the Penan communities of Long Tevenga, Ba Peresek, Long Adang and

Long Gita, unanimously disagree with the MTCS Certificate for Samling Company for the area within our village territory as shown by our community map. In the area of our Penan village map, there are various interests such as traditional medicines, ipoh poison tree, saltlick, fruit tree, sago clumps, rattan, river where to find fish and animals on land, Living Land, we do not want everything to be destroyed.”[51]

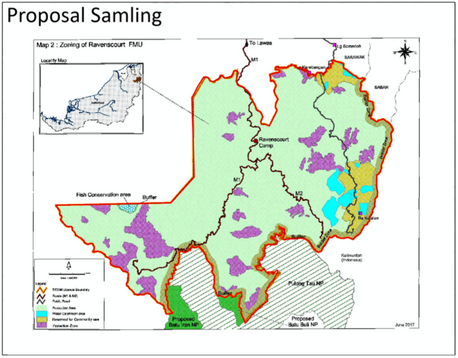

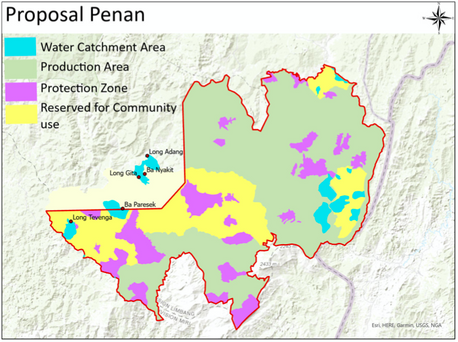

A map from Samling’s Forest Management Plan (Figure 13, top) leaves the Penan communities off the map entirely. It also does not show any Community Use Zone (CUZ) marked for the Penan. These are areas within the forest that are set aside for the use of local communities for their livelihoods and traditional activities. Under FDS procedure, and therefore under MTCS, there is a requirement to identify and demarcate CUZs in the Forest Management Plans of FMUs.

Long Adang

Figure 13: Analysis of Samling map vs Penan proposal

Map from Samling’s Forest Management Plan from June 2017 does not include any Penan communities or CUZs.

Map showing where Penan communities, protected forest, and CUZs should be in relation to the Ravenscourt FMU according to Penan communities.

The communities learned of the Ravenscourt FMU and MTCS certification in the context of its ongoing re-evaluation. The village received a letter from Samling and SIRIM in July 2020 requesting a meeting, but the purpose of the meeting was unclear. The communities did not attend this meeting, explaining: “since we did

not fully understand the purpose of the meeting, we did not go. Secondly, we are very worried about the COVID-19 pandemic.” This is not uncommon, as communities are concerned that agreeing to a meeting could be misconstrued as consent for logging.

Suling Selaan FMU

T/0412 and T/0411

Figure 14: Suling Selaan FMU and overlapping and nearby community territories

Suling Selaan FMU T/0411 & T/0412

Long Lamam Land

Long Ajeng/Long Murung Land

Long Moh Land

Jamok Land

N

The Suling Selaan FMU contains two logging concessions: T/0412 and T/0411. The Penan have a long history of resisting logging in this area. When Samling entered the area around the village of Long Ajeng in the early 1990s, over 1,000 Penan participated in a roadblock that prevented Samling from building its main timber road into the area. The Penan maintained the blockade for several months before it was destroyed by the government’s special police unit and the military on September 28th, 1993. More than 200 people were injured and three Penan died as the result of police violence.[52]

In 2004, T/0412 was the first concession to be certified under MTCS in Sarawak. Following the certification, many headmen in the area, including Bilong Oyau, the Headman of Long Sait and a leader for the Penan communities in the area, sent a letter to MTCC on January 25, 2005, criticizing the lack of consultation with the local communities and requesting MTCC to revoke the MTCS certification.[53] This MTCS certificate expired in 2009.[54]

At an unknown time, concession T/0411 was certified for legality under STLVS. A GFS audit from 2019 confirmed that Samling had not conducted social impact assessments for all villages and that the company had no agreement with the three villages of Long Ajeng, Long Lamam and Ba Data Bila:

“Samling Plywood (Baramas) Sdn. Bhd. has not conducted a formal Social Assessment separate to the EIA that included an evaluation of 7 of the longhouses associated with the T/0411 licensed area. The Kenyah and Penan tribe settles [sic] the region. The Penan villages of Ba’ Ajeng, Long Lamam, and Data Bila were not visited under the Social Assessment to develop an agreement. Since Samling Plywood (Baramas) Sdn. Bhd. has not established a formal agreement with the 3 mentioned Penan villages, no logging operations are conducted in the areas claimed by the longhouse communities.”[55]

In August 2020, Penan leaders and KERUAN Organisation sent further letters to SIRIM requesting information about the certification and indicating their rejection of logging on their territory.

It appears that the legality certification under STLVS was terminated at some point, as Samling seems to be transitioning to the legally required MTCS certification. Current assessments undertaken in the area indicate that MTCS certification for this FMU is likely underway.

Historical Image of Long Ajeng protest 1992

Long Ajeng, Long Lamam, and Long Murung

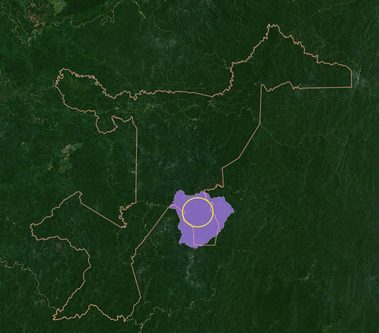

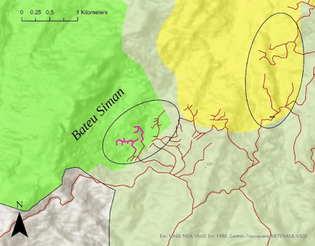

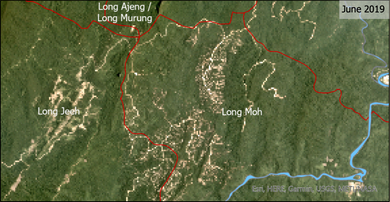

On February 7 and 9, 2021, Penan community leaders of Long Ajeng and neighboring Penan villages of Long Lamam and Long Murung confronted Samling workers about the logging they had discovered in their territory. Their territories are within the UBFA.

These communities then lodged a police report about the logging activities on March 5, 2021. A blockade was erected on September 9, 2021, to stop Samling extracting timber.[56] When Samling encroached further and entered the proposed core protection zone of the UBFA in May and June 2022 (see Figures 15-17), the communities filed another police report, consulted their lawyer and alerted supporting NGOs. The logging was taking place in a culturally and ecologically sensitive area called the Batu Siman mountains.

In July 2022, just before the communities started rebuilding their blockades, Samling withdrew their machinery from the area.[57]

Figure 15: Analysis of logging

road encroachment

Upper Baram Forest Area

Agricultural zone

Buffer zone

Core zone

Logging roads until April 2022

New logging roads May-July 2022

Figure 16: UBFA, Samling FMUs and community territories

Suling Selaan FMU T/0411 & T/0412

Long Lamam Land

Long Ajeng/Long Murung Land

Upper Baram Forest Area

Area of Interest

N

Figure 17: Encroachment near the Batu Siman mountains

Before May 2022

Area of Interest

Batu Siman

After May 2022

Jawa Nyipa showing the impacts of the logging on his community’s territory, July 2022

“We never gave Samling an entry authorisation. Many times, we asked them to stop working in our area. Samling did not listen to a single word from us and has been taking timber from our land up until now. Now we ask them one last time to stop and we want compensation for the damage they have done on our land.”

— Jawa Nyipa, headman of Long Ajeng [58]

Penan communities protesting Samling logging on their territories, September 2021

Long Moh

Figure 18: Long Moh territory overlapping with Gerenai and Suling Selaan FMUs

Gerenai T/0413 FMU

Suling Selaan FMU T/0411

Long Moh Land

N

The Kenyah community of Long Moh also experienced logging without their consent, even after being consulted by Samling. Long Moh has territory in two FMUs operated by Samling: the Gerenai FMU and the Suling Selaan FMU.

SIRIM’s 2022 audit report of the Gerenai FMU substantiates the existence of “native issues” with Long Moh, and reports that these issues were not handled according to the Procedure for Conflict Resolution. The GFS audit for concession T/0411 (Suling Selaan FMU) from 2019 identifies a “lack of agreement” with the community of Long Moh as a “minor gap.”[59]*

The Bekia area is a culturally sensitive site within the territory of Long Moh and the UBFA. It is also within the boundaries of the Suling Selaan FMU and was logged by Samling without community consent.

Sign that reads ‘Do not steal wood

from the Long Moh village area’

*Compliance is defined when all applicable criteria are observed to be compliant. A Minor Gap to any indicator does not constitute non-compliance to a criterion. “A major gap” to any applicable indicator does reflect non-compliance to a criterion. Compliance for a criterion where multiple minor gaps are identified in indicators under the criterion may reflect non-compliance to the criterion.

Figure 19: Analysis of logging activities In Long Moh 2017-2021

Communities

River

Extent Indicator

Satellite imagery between 2017 and 2021 shows a web of logging roads and logging activities creeping into the traditional territory of Long Moh (see Figure 19). In July 2020, Long Moh community members discovered that Samling had encroached into the Bekia, Ampai, and Seru’en areas. They sent a letter to Samling in September 2020, demanding compensation and action. After no response, they sent another letter to Samling in February 2021, this time signed by 300 community members and CC’d to MTCC, SIRIM and Forest Department Sarawak.[60]

The letter states that during a meeting between the residents of Long Moh and representatives from Samling on June 18, 2018, “Mr. Fam Chee Kiong promised that [Samling Timber] would not enter the Bekia, Ampai, and Seru'en areas without holding any consultation with the residents of Long Moh.”[61] However, based on the community’s ground surveys, “it is true that the entire forest and NCR land in these areas have been encroached and destroyed by Samling Timber.”[62] The letter also states that the logging camp manager, Mr. Lai Kam Wen, had agreed to compensate Long Moh for this encroachment during a meeting held on September 24, 2020.

Logging trucks in the territory

of Long Moh, October 2020

Trees from the territory of Long Moh stamped by Samling, October 2020

In response, Samling representatives sent a letter to Long Moh claiming that they never agreed to not carry out logging in the Bekia, Ampai, and Seruen areas. Samling’s letter not only denies the agreement to not log certain areas, it also threatens legal action against the community. As of publication, Long Moh has not received compensation from Samling.

Samling’s imprudent action will not only destroy our primary jungle but also will wipe out our history. An area which is considered to be sacred and holds our ancestors’ belongings has signs of trespassing and destruction.”

— William Tinggang, Long Moh.[63]

Photos of unwanted logging documented

by Long Moh community, October 2020

Long Moh community protesting Samling

Legal Intimidation

Beyond the documented conflicts with communities, Samling’s legal threats and demands against Indigenous communities and a small grassroots organization have had an intimidatory effect and have concerned many onlookers in Sarawak and internationally.

Samling has sent letters to communities threatening legal action and has resorted to suing a local NGO for reporting opposition to logging. Some argue that this strategy attempts to silence community concerns and puts at risk the right of civil society to publish or report on those concerns as a matter of public interest.[64]

Indigenous Kenyah and Penan communities in the Baram watershed opposing logging on their territories tried to establish a dialogue with the concession holders and relevant government authorities.

When those attempts failed, they turned to two local non-governmental organizations (NGOs), SAVE Rivers and KERUAN Organisation, for support. These organizations have a long history of working with Indigenous communities and are themselves managed and led by Indigenous people from Northern Sarawak. Penan communities of the Limbang watershed also turned to these organizations after learning that logging concessions overlapped with their native territories.

SAVE Rivers and KERUAN Organisation helped communities reach out to the relevant government agencies and Samling personnel. When all communication channels were exhausted, and after nothing had changed on the ground, the NGOs began publishing reports in the public domain about Indigenous communities’ grievances regarding Samling’s logging operations.

Stop the SLAPP protest outside Miri High Court

Stop The SLAPP supporters in Long Semiyang

In July 2021, Samling Plywood Miri Sendirian Berhad and Samling Plywood Baramas Sendirian Berhad filed a defamation lawsuit against SAVE Rivers for publishing those reports.[65]

The United Nations Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre have recognized that this suit may be classified as Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation (SLAPP).[66] SLAPP suits are intentionally designed to avoid accountability by preventing public dialogue and intimidating local resistance.[67]

Samling’s Statement of Claim for the lawsuit demanded an apology, an injunction stopping SAVE Rivers from reporting community claims and damages in the sum of RM 5 million, or 1.1 million US dollars. This would have bankrupted SAVE Rivers and its directors.

Stop The SLAPP supporters in Australia

Stop The SLAPP supporters in the United Kingdom

Stop The SLAPP supporters In Sarawak

Samling also sent letters to communities threatening legal action. These letters were in response to letters sent by the communities expressing their dissatisfaction with the consultation process or opposition to logging operations on their land. In a letter dated March 26, 2021, to the communities of Long Moh, Samling COO James Ho Yam Kuan wrote:

“[T]here is absolutely no basis for your claim for compensation for any alleged encroachment, damage and/or destruction. We reserve our right to bring legal action.”[68]

A letter sent from James Ho Yam Kuan regarding the Penan communities in the Ravenscourt FMU to on April 14, 2021, uses similar language, as does a letter regarding the Penan communities of Long Ajeng, Long Murum, and Long Lamam, sent by Samling CEO Lawrence Chia Kee Loong on April 9, 2021.[69]

These letters illustrate Samling’s approach to community grievances, which is one of denial and legal threat rather than engagement and proper investigation of complaints.

Stop The SLAPP protest In Switzerland

Support poster by local artist

Shaq Koyok

The SLAPP suit against SAVE Rivers, although eventually withdrawn before trial, necessitated the diversion of significant organizational resources by a small community-based NGO, and time and effort by its staff and board members towards preparation for court proceedings. But, rather than having a chilling effect on community campaigns, Samling’s legal action against SAVE Rivers sparked an international solidarity movement. This included extensive media coverage and a petition with more than 30,000 signatures.[70] More than 160 local and international organizations joined the call for Samling to drop the suit, and more than 8,000 people sent emails expressing their concern to Samling’s CEO.[71]

In August 2023, Samling CEO Chia Kee Loong filed a police report against SAVE Rivers and its board members.[72] In the report, he accused SAVE Rivers of spamming his email address with emails petitioning him to drop the suit against SAVE Rivers. These emails were not sent by SAVE Rivers, but by international supporters in opposition of the SLAPP suit.

SAVE Rivers directors and lawyer called to the police station

Stop The SLAPP protest at London Zoo

The police report also accused SAVE Rivers of disturbing the peace during court proceedings in May 2023. These proceedings were originally scheduled to be the trial dates for the defamation suit against SAVE Rivers, however, a few days before the trial, the trial was delayed and instead, lawyers for both sides met at the court to determine dates for the rescheduled trial. During that meeting, supporters of SAVE Rivers gathered at the court building and performed traditional song and dance in a peaceful and respectful gathering. It was this gathering that was the subject of the Samling CEO’s police report.

After three adjournments, final trial dates were set to commence on September 18, 2023. On the morning of September 18, Samling formally withdrew the suit, releasing a joint statement with SAVE Rivers.[73]

None of the allegedly defamatory content was edited or taken down, and Samling received no damages or apology from SAVE Rivers. Communities understandably viewed this withdrawal as a major win for forest defenders.

“This is a huge victory for SAVE Rivers and the communities they support, and a humiliating backdown for Samling. SAVE Rivers and the communities stood and will continue to stand in solidarity with each other. No one thought that we could win against such a powerful company, but we proved everyone wrong.”

— Boyce Ngau, vice-president of GCRAC commenting on Samling’s withdrawal [74]

Documented Unsustainable Environmental Practices

Photograph of Samling logging operations taken by Long Moh community in October 2020

Timber sourced from Samling should not carry the “sustainable” label because of the numerous Indigenous rights concerns listed above. However, even without taking evidence from a human rights perspective into account, importer countries and international buyers should take note of Samling’s questionable environmental record - a record which disproves their claim to the “sustainable” label.

This report has already covered recent logging in the UBFA, an important conservation zone and wildlife corridor. Samling has also logged a proposed wildlife sanctuary, leveled forests in contravention of forest conversion rules and contributed to a significant increase in flooding risk.

Forest cleared by Samling up to 50 metres at the side of the road in breach of normal limits in Suling Selaan FMU, as reported by Earthsight in 2010

Sungai Moh Wildlife Sanctuary

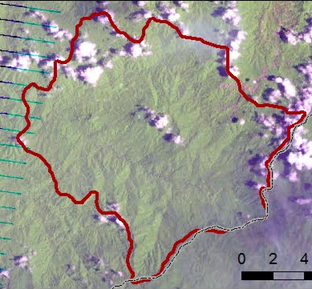

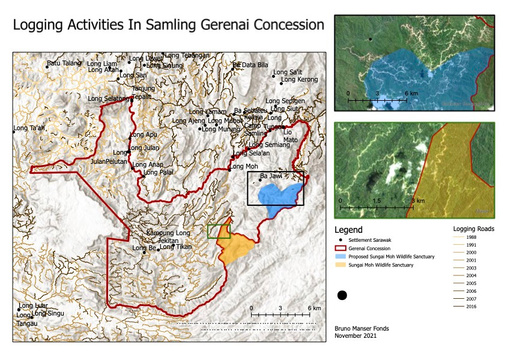

Samling logged an area that was originally slated to become a Wildlife Sanctuary in the Sungai Moh area.

The Sarawak government initially proposed the Sungai Moh Wildlife Sanctuary for an area in the northeastern part of what is today the Gerenai FMU, according to a map from FDS from 2010 (see Figure 20). This area is also claimed by the local Penan community of Ba Jawi. At that time, the forest in the proposed protection area was still intact and there were no logging activities taking place

(see Figure 22).

Samling first began to construct a logging road into the proposed Sungai Moh Wildlife Sanctuary area in September 2010. By February 2012, Samling was logging intensively inside the area. By 2014, most of the wood resources inside the area had been exploited (see Figure 22).

According to a map of Samling’s Forest Management Plan for the Gerenai FMU from 2019 (see Figure 21), the location of the Sungai Moh Wildlife Sanctuary was later moved to a region southwest of the initial location, now on Long Moh land. Samling also built roads encroaching into the area of the new sanctuary location (see Figures 23 and 24).

Figure 20: Historical location of

Sungai Moh Wildlife Sanctuary

Figure 21: New location of Sungai Moh Wildlife Sanctuary sourced from Samling Forest Management Plan

Figure 22: Progression of logging in the proposed Sungai Moh Wildlife Sanctuary between 2010-2014

Satellite image shows unlogged forest in February 2010, in proposed Sungai Moh Wildlife Sanctuary.

Logging roads start to develop in September, 2010.

Logging activities intensify in February, 2012.

By February 2014 Samling has logged the entire area of the proposed Sungai Moh Wildlife Sanctuary.

Figure 23: Analysis showing encroachment into both old (blue) and new (orange) locations of

the sanctuary

Figure 24: Analysis showing encroachment into the new location of the sanctuary

Forest Conversion

Forest conversion (the clearing of forests for other purposes, usually agriculture) of more than 5% of the total area of an FMU is prohibited in the MTCS scheme.

However, in the Gerenai FMU approximately one quarter (47,859 hectares) of the FMU is designated as a plantation. This means it has recently been, or is in the process of, being clearcut to establish oil palm plantations. This is referred to in Samling’s Forest Management Plan for the Gerenai FMU as “[an] area designated as provisional leases for agricultural development… will at some time be excised from the FTL [Forest Timber License]”.[75]

The excised area of 47,859 hectares is far in excess of the allowed 5% limit. To resolve this non-compliance, SIRIM has presumably accepted the exclusion of the Provisional Lease area from the scope of certification, even though the unit of certification under MTCS is the full FMU.[76] The main FMU Camp, Gerenai Camp, lies within the excised area.

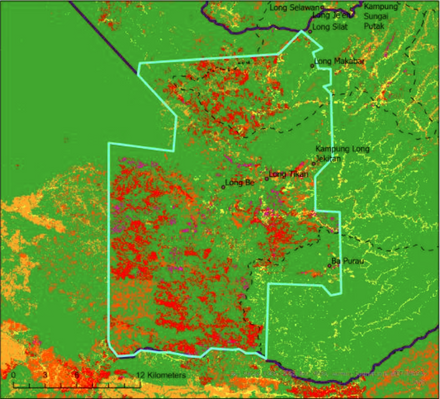

Figure 25 shows that the area has been logged intensively since 2018, predominantly by Samling, but also by some other companies, most likely subcontractors. The images indicate the clearing of forest to establish a non-forest zone, in this case agricultural plantations.

MTCS requires that “conversion from natural forest… shall not include any High Conservation Value areas”.[77] If an HCV assessment was conducted prior to logging, it is not available publicly. The area being converted contained significant intact, unlogged natural forests and provided significant resources for local communities and valuable habitat for wildlife. It is highly likely that this area contained multiple High Conservation Values.

Oil palm plantation in Sarawak

Figure 25: Extensive deforestation in excised area of Gerenai FMU

Samling

Excised Area Gerenai

Year of deforestation:

No deforestation/before year 2000

2000-2006

2007-2012

2018-2019

2020-2021

N

It is now mandatory for all FMUs in Sarawak to be certified under MTCS or FSC. The conversion of a large area of intact forest into non-forest use is a gross violation under each scheme, and would disqualify the FMU from certification. That this FMU has been certified by the MTCS, after audits conducted by SIRIM, illustrates that the enforcement of the standards is defective.

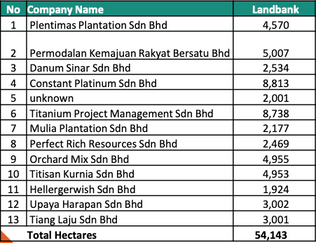

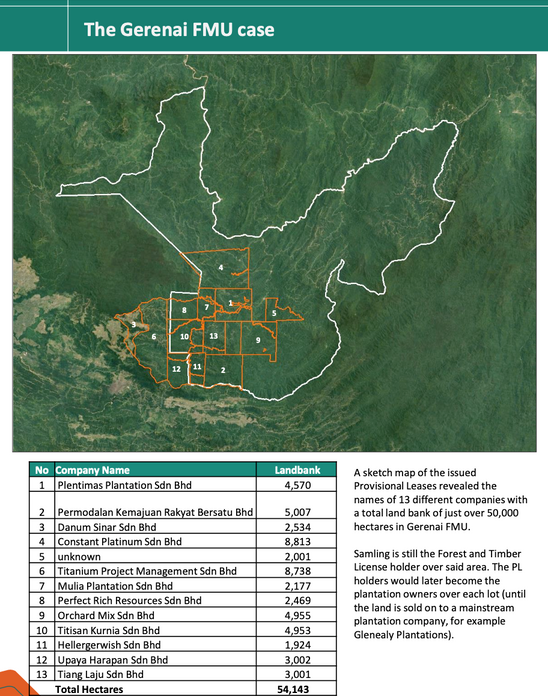

The excised area will be converted into oil palm plantations (see Figure 26). It has been divided into 13 Provisional Leases for oil palm plantations that have been given to companies with strong political ties, including four companies that are the land clearing operators for Samling Plywood (Miri).[78]*

In Malaysia, the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) Certification Scheme is now mandatory. According to MSPO, establishment of new plantations must not involve any conversion of natural forest, protected areas or High Conservation Value areas after December 31, 2019, and companies must complete EIA, SIA and HCV assessments prior to the development of the land.[79] The palm oil from this excised area will therefore fail to meet MSPO requirements. It will also fail to meet the standards of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), and the new EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) requiring products to be deforestation free.**

*Three of the 13 Provisional Leases fall outside of the FMU area.

**The EUDR requires companies trading in cattle, cocoa, coffee, oil palm, rubber, soya and wood, as well as products derived from these commodities, to ensure the goods do not result from recent (post 31 December 2020) deforestation, forest degradation or breaches of local environmental and social laws.

The excised area of the Gerenai FMU presents two significant conundrums: the forest conversion excludes any timber from the area being sold under MTCS or FSC, however certification under these schemes is mandatory for all FMUs.

Neither does the palm oil from the area qualify to be sold under MSPO, however, the MSPO is mandatory for all oil palm plantations.

This illustrates the contradictory nature of forest management in Sarawak. FDS is responsible for tendering the logging and oil palm concessions. It has also initiated the requirement for FMUs to obtain forest certification. The government makes commitments to protecting their forests and establishes policies intended to sustainably manage forest resources, while simultaneously permitting gross violations of these commitments and policies.

Figure 26: Issued Provisional Leases showing the names of 13 different companies with a total land bank of just over 50,000 hectares, primarily within the Gerenai FMU. Map obtained from the Land and Survey office.

Plantations

Samling also manages a number of Licenses for Planted Forest (LPFs) in Sarawak. These LPFs are often managed by one of its subsidiaries, Samling Reforestation (Bintulu) Sendirian Berhad. These “Industrial Tree Plantations” are essentially tree farms, where natural forest areas have been cleared for replanting with fast-growing, often non-native tree species that are cultivated and harvested for sale as timber products. This practice greatly harms forest health and biodiversity. It is not reforestation in the sense of restoring original biodiversity, but instead the clearing of natural forest to make way for further commercial forestry in a manner which actively prevents native species from recovering. Samling recently received a permit for a pilot carbon trading initiative in of it its LPFs.

Figure 27: Samling's LPFs in Sarawak according to available data

Flooding

Flooding at Long Tungan, early 2021

Samling is the main concession holder in the Baram watershed. According to a 2023 study of the Baram area: “Since 2008, flooding incidents have increased steadily with compounded frequency and extremity annually.”[80] The same study found that overlogging in the Upper Baram was a contributing factor to this increase.

At least six villages in the Lower and Upper Baram watershed have been significantly affected by these flooding disasters, with structural loss and damages, adverse health impacts, personal loss and grievances, social disruptions and financial burdens.

Deforestation and logging are often linked to increased flooding. Healthy forests filter water, reduce erosion, regulate rainfall, recharge

groundwater tables and buffer against the impacts of droughts and floods.[81] When watersheds are unable to properly filter water and regulate water supply, erosion, flood and landslide risks increase.

A 2014 EIA conducted for the Gerenai FMU confirms that impacts during the felling stage include runoff increase, which “may lead to flash flooding during intense rainfall” and that “the risk of flash flooding in the downstream area will increase.”[82] Communities also allege that, in contravention of forestry regulations, Samling extracted timber from riverbanks, and have provided photographs of such areas. Such extraction would negatively impact the ability of the watershed to regulate flooding.

Documented Shortcomings, Disparities and Factual Errors in Impact Assessments

Community consultation

Social Impact Assessments (SIAs), Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs), and High Conservation Value (HCV) Assessments are a crucial step in determining whether and how to initiate a wide variety of projects.

Evaluating the impact that a logging concession will have on the environment and people is vital to understanding whether a project is desirable, viable, and feasible, and how to avoid or mitigate potential damage. Without properly understanding the impacts, a project is much more likely to encounter obstacles, create community opposition, and adversely impact ecosystems and people.

Weak Impact Assessments

“The real fact is that the kampong [village] folks don't understand. These consultants, however, rushing with their presentation and what they present, it is beyond their experiences. Moreover, some are illiterate even though the consultants tried to explain through slide presentation.”[85]

Social and environmental impact assessment processes in Sarawak historically exclude the very communities they are evaluating. Unlike under federal processes, there is no public participation requirement for EIAs in Sarawak.[83] Common issues with EIAs and SIAs include lack of clarity, opaque procedures, inaccessible documents, and low-quality participation.[84]

Impact assessors regularly fail to adequately communicate their objectives. Community members are often confused about what the consultants are doing and why they are there. As one leader from the Gerenai area explained,

Impact assessments are notoriously difficult to access, both from government agencies and from Samling. Communities are routinely unable to access reports, even when they formally request copies, including maps of their own territories and mitigation requirements.[86]

In June 2020, the Gerenai Community Rights Action Committee (GCRAC) formally requested copies of impact assessment reports for the

Baram Heritage Survey technicians in training

Gerenai FMU from the Natural Resources and Environment Board (NREB), the Sarawak state agency in charge, and did not receive a response. GCRAC formally requested copies of impact assessments reports for the Gerenai FMU from Samling in August, 2021, but again, did not

hear back.[87]

Impact Assessors also anecdotally allege that they are unable to access impact assessment documents from the NREB to conduct background research on an area. The NREB tightly controls access to EIAs and SIAs conducted in Sarawak. Sometimes it is possible to access some physical copies of the reports at their offices, but they typically do not allow copies or photos of the documents to be made, and no one is allowed to take the documents out of the office.

Without access to these documents, communities are unable to verify or counter the results of impact assessments and, as a consequence, cannot exert their Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC).

It also makes it difficult for assessors to conduct background research, which can impact the quality of assessments.

Assessments sometimes fail to comprehensively describe impacts. The summaries of SIAs in Samling’s Forest Management Plans regularly highlight the positive impacts of logging such as road access and job opportunities for local communities, but often fail to mention negative impacts such as increased risk of floods, poor water quality, lack of timber for community use or reduced availability of game and forest products in logged forests.[88]

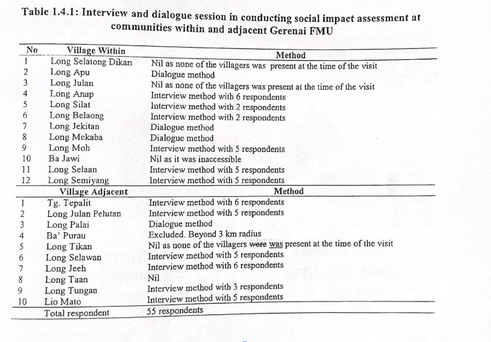

Assessments often fail to adequately consult a wide range or high number of community members. This is clearly visible in auditing reports and impact assessments in the Gerenai FMU. For example, the 2018 SIA for the Gerenai FMU notes that a total of 55 respondents were interviewed in an area with an estimated population of at least 11,472 (see Figure 28).[89]

Community consultation

Figure 28: Table from the Social Impact Assessment from 2018 for the Gerenai FMU. The table shows no one was consulted in 5 out of 22 communities and very low participation rates in most communities.

The 55 respondents were largely a homogenous group: 94% were male, and 63% were above the age of 55. The report notes that no one was interviewed in 5 of the 22 villages listed. In two of the villages only 2 people were interviewed. The author of the report explains that the SIA was conducted by two teams who split up to visit different communities. The author included community grievances that he heard into the SIA, however, he excluded the grievances heard by the other team in order to “prevent misconception.”[90]

In the Baram area, failure to secure community participation concurs with a lack of trust regarding industrial logging and consultation processes. The trip report from the 2014 SIA notes that the communities of Long Palai, “stressed that just because they are cooperating, it doesn’t mean that: agree [sic] to extend timber license, agree that the certificate to be awarded to the company.”[91] Like many villages in the Baram area, they distrust assessment processes due to a history of encroachment and the failure of the company to properly consult and

obtain consent.

As one leader of Long Moh described: “We are careful with any meeting invitations from the logging company. We are fed up with the dirty tricks of those who often look for opportunities to ‘obtain’ our Free, Prior and Informed Consent in malicious ways. In the past, when we attended meetings with the logging company [Samling], they often took our presence there as an agreement to all their wishes or agenda without properly informing and consulting us via proper minutes of the meeting or with any other relevant documents.”[92] The interviewee went on to explain that when people refused to fill out the questionnaires during a SIA consultation, the consultants tried to incentivize them by giving the first 10 people to fill out the questionnaire a prize, or “lucky draw”.

As described in Part II, Samling has violated agreements with Long Moh. The community is worried that any future agreements will be violated, and that their participation will be equated with consent.*

*Communities are right to think that their participation may be misconstrued as consent. Samling used the name of one of the SAVE Rivers directors they filed a defamation suit against on its CSR web page to promote how they cooperate with local NGOs and communities.[93]

Comparison to Community-Led Assessment

Comparing impact assessments and public summaries from the Gerenai FMU to a community-led assessment conducted in the same area demonstrates failures in the impact assessment processes. Data collected by the communities during the Baram Heritage Survey (BHS) is more abundant and accurate.

The BHS was a survey conducted in six communities of the Baram area in 2020 and 2021, including three that have territories in the Gerenai FMU and three that have territories in the Suling-Selaan FMU. In those six communities, about 80% of the permanent population was interviewed regarding land use, hunting, fishing, agriculture, and livelihood.[94]

A 2014 EIA from the Gerenai FMU underplays the value of forests for communities and diminishes their reliance on forest resources for nutrition, falsely claiming that hunting

mammals is “becoming less common” and that “fishing is not an important activity.”[95] Samling’s public summaries for its LPFs similarly misleadingly report that there is, “no real dependence [by local communities] on the forest products available in the MTCS area or indeed on those provided by the whole LPF.”[96]

The public summary for the Paong LPF continued to argue that, “Although wildlife still supplements the diets of some people, and wild vegetable and wild fruits are still gathered, what activity there is – primarily hunting, fishing and foraging for wild vegetables – is supplemental. It is abundantly clear that there has been little real negative socio-economic impact by the activities within the PAONG MTCS area on the nearby communities.”[97]

BHS field team for one village

The results of the BHS survey, however, clearly negate these claims. In the BHS, 100% of the 111 people interviewed eat wild meat and fish, 71% regularly go hunting, 93% regularly go fishing, and 92% regularly consume wild-collected fruit.[98]

The BHS also found conflicting results regarding the positive impact of logging. The 2014 EIA states that over 100 people from local communities regularly work for the timber company, however the BHS found zero people employed by the timber company: all household incomes are reliant on traditional livelihoods such as agriculture, hunting, fishing, and foraging.[99] The EIA claimed that logging would raise household income, however the BHS found no increase in household income six years after the EIA was conducted.

The BHS also found significantly more wildlife. The 2014 EIA states that totally protected